The Alien Becoming the Familiar

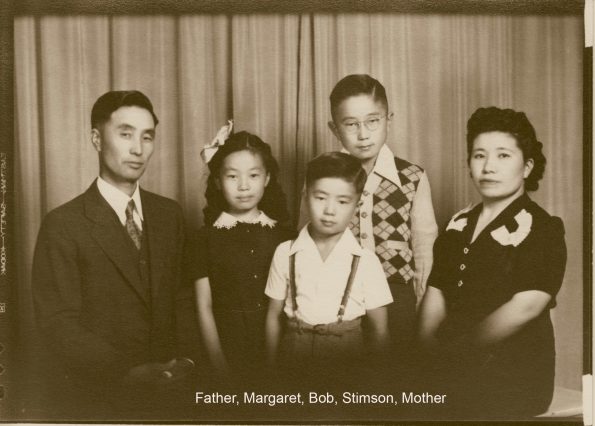

By Margaret Kokka

During our fifty plus years of residing in north Berkeley, my family and I have had the opportunity to sample a wide variety of cuisines. Nearly a decade ago, strolling down Solano Avenue we counted nearly 30 restaurants offering Indian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Mexican, Vietnamese, Chinese and variations of all- American meals with the exception of a Subway sandwich franchise, no fast food outlets.

Often visiting the farmer’s markets or standing in line at Monterey Market we would join brief conversations regarding which of the apples, oranges or mushroom were in season or the relative merits of almond, lactose-free, goat, or soy milks. North Berkeley has been designated the Gourmet Ghetto and its local denizens are acquainted with the latest diet fads whether paleo, vegan, low fat, gluten-free, Mediterranean and supermarkets have responded by offering specialty foods catering to these diets. In this land of plenty it seems our mantra is “we live to eat.”

It wasn’t always that way.

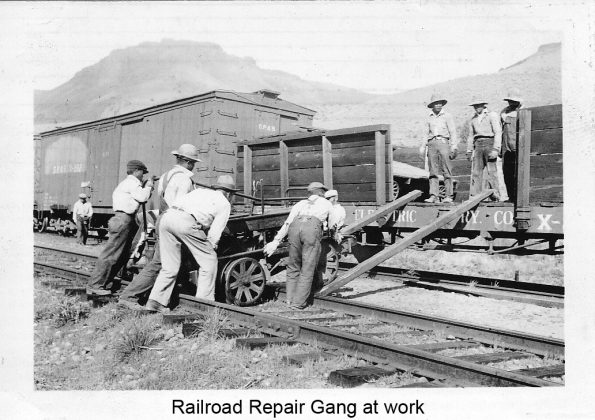

Our country faced a serious national shortage of food during the Great Depression of the 30’s when unemployment was endemic, millions went to bed hungry and soup kitchens opened to meet this emergency. My siblings and I, born in the 1930’s were spared this plight since our father continued working for the Southern Pacific railroad.

Our country faced a serious national shortage of food during the Great Depression of the 30’s when unemployment was endemic, millions went to bed hungry and soup kitchens opened to meet this emergency. My siblings and I, born in the 1930’s were spared this plight since our father continued working for the Southern Pacific railroad.

Both my parents were recent immigrants from Japan and our daily meals might have been considered alien and strange in appearance, taste, and smell by the general population. I recall the flat, orange-colored whole dried cuttlefish roasted over the top of the black cast iron stove and its salty fishy aroma tickling our nostrils. There was another Japanese food delicacy, natto. Several pounds of soybeans were rinsed, placed in a round flattened ceramic bowl, covered, wrapped in a dishcloth and moved to a warm spot behind the stove where it was left to ferment. After several weeks we’ would uncover this bowl revealing a creamy mash, its overpowering smell filling the kitchen. We’d finish off a bowl of fresh hot rice with a spoonful of natto trailed by its sticky strands, Clearly an acquired taste!

Both my parents were recent immigrants from Japan and our daily meals might have been considered alien and strange in appearance, taste, and smell by the general population. I recall the flat, orange-colored whole dried cuttlefish roasted over the top of the black cast iron stove and its salty fishy aroma tickling our nostrils. There was another Japanese food delicacy, natto. Several pounds of soybeans were rinsed, placed in a round flattened ceramic bowl, covered, wrapped in a dishcloth and moved to a warm spot behind the stove where it was left to ferment. After several weeks we’ would uncover this bowl revealing a creamy mash, its overpowering smell filling the kitchen. We’d finish off a bowl of fresh hot rice with a spoonful of natto trailed by its sticky strands, Clearly an acquired taste!

In my lifetime, the second serious trauma facing our country was World War II. Everyone joined in the war effort buying war bonds, watering their victory gardens, saving aluminum foil and rubber bands and accepting the sacrifices for the duration of the conflict. Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, all persons of Japanese descent were rounded up and our family joined 120,000 others inside concentration camps scattered throughout the desert areas in the interior of the country. During the three years we spent in Minadoka, Idaho, the government provided all the basic necessities: shelter, clothing and food.

In my lifetime, the second serious trauma facing our country was World War II. Everyone joined in the war effort buying war bonds, watering their victory gardens, saving aluminum foil and rubber bands and accepting the sacrifices for the duration of the conflict. Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, all persons of Japanese descent were rounded up and our family joined 120,000 others inside concentration camps scattered throughout the desert areas in the interior of the country. During the three years we spent in Minadoka, Idaho, the government provided all the basic necessities: shelter, clothing and food.

All the internees (as we called ourselves) were fed in a central mess hall, similar to those in army camps. Food prepared by untrained and inexperienced cooks was frequently unappetizing and strange. I can recall entering the chow line, the strong smell of soy sauce rising from the large aluminum pots boiling on the stove. As I approached the server, a large ladle scooped a pink and black jumble of squid tentacles onto my plate. Rubbery, steaming, and in my imagination, still squirming. I gazed down in dismay and was unable to bring any to my lips.

I also remember a piece of grey-pink cut of meat covered in innumerable bumps with the underside curved into a cup shape; this offering coalesced into an unappetizing piece of unpeeled calf’s tongue. Even now, a half century later, certain foods trigger memories associated with our incarceration during WWII. Camp officials parceled out multiple tins of apple butter and paper bags filled with dried apricots— tough, wrinkled and hard enough to use on target practice. Now these memories remain as a distant shared experience punctuated with wry humor.

Upon our release from Minadoka, we celebrated our first home cooked meal outside the confines of our GI (that is government issued) camp. Within our family we coined that meal as our Million Dollar breakfast: fry up two rashers of bacon, two eggs sunny side up, spread over a mound of hot rice, pour some soy sauce over everything and eat like a millionaire.

Upon our release from Minadoka, we celebrated our first home cooked meal outside the confines of our GI (that is government issued) camp. Within our family we coined that meal as our Million Dollar breakfast: fry up two rashers of bacon, two eggs sunny side up, spread over a mound of hot rice, pour some soy sauce over everything and eat like a millionaire.

It has been a long journey from the dried cuttlefish and natto of my childhood to the cuisines of the Gourmet Ghetto in Berkeley. In that time I have seen Japanese flavors associated with sushi, tofu, miso soup, teriyaki chicken, instant ramen and tempura prawns become part of American taste. Many have mastered the art of using chopsticks although none as adroit as Mr. Miyagi (of the Karate Kid fame), whose dexterity included snaring a fly in mid-flight.

Truly, the alien has become the familiar.

![]()

Margaret Kokka

Margaret Kokka is married with two children. Her career has focused on children and families. She taught in Roosevelt Jr. High in Richmond, evaluated children in the Child Development Center in Oakland’s Children Center, served as Executive Director of West Coast Children’s Center and filled in as the Interim Director for three nonprofits.

Margaret Kokka - September 12, 2019 @ 4:18 pm

Thank you for your thoughtful and heartfelt response. We share the memories of the immigrants’ struggles through our parents as they dedicated their lives to provide a hopeful and brighter future for us, their children. I agree that the current plight of many new-Americans suffering the “unjust actions poured upon our country’s immigrants” is shameful and totally counter to the values dear to our nation.

Our appreciation for our parents leaving their homeland, learning a new language, and surviving in an unknown culture has grown with a deeper understanding of their courage and belief of a better life in their adopted country.

MARLENE MOON - September 10, 2019 @ 12:04 pm

Ms. Kokka,

What a rich plate of history you have given us to taste. A timely remembering for the plethora of unjust actions pounced upon our country’s immigrants. My mother’s family, running from the hysteria and death from hoards of Russian intruders upon their country, fled from Yugoslavia. My father’s family ran from Ireland to stave off the profound hunger during its potato famine. I am first born, American. The plight of so many of now-Americans still rings clearly in my heart and soul. It is for them, our beloved country was (and is being) built. When I look back at my childhood I can still touch the deep furrows of my grandmother’s face. I did not know my paternal grandmother but learned she lost several of her beloved children during the voyage across the Atlanta; my father would never be the same for it.

I want to thank you for your voice. I want to thank your parents for coming here. I’m not sure many of us would have that kind of courage these days.