Sweet Alabama

By Barbara Ridley

My social media feeds were full of calls to “Boycott Alabama!” “Leave!” “Never go there!” Andy Borowitz, one of my favorite political humorists, posted: “Americans given new reason never to go to Alabama.” I saw lots of Likes and Ha-Ha emojis. And then disparaging comments along the lines of: “Stop writing insults about Alabama; they’re 50th in education. They can’t read that shit.” More ha-ha’s.

Previously, I might have shared these posts, and laughed at the jokes, and clicked on those same emoji’s. I understood the outrage. The Alabama State Senate had just passed the most restrictive anti-abortion law in the nation.

But this law was passed immediately after my first visit to Alabama. I had spent two days in Montgomery, and loved it. I wanted to stay longer; I was already yearning to return.

Make no mistake: this is a terrible bill. Voted into law by a posse of all-white, all-male Senators, it makes abortion illegal at any stage of pregnancy, with no exceptions for rape or incest. It threatens potential life in prison for any doctor who performs the procedure. I’m staunchly pro-choice. I believe the government has no role in a decision that should be left to a woman and her medical provider. I can’t stand the hypocrisy of those who claim to be acting out of concern for the “life” of the fetus, but who demonstrate no interest in promoting healthcare, childcare, or anti-poverty programs once the child is born. So yes, I’m mad as hell.

Yet I loved Alabama—much to my surprise.

My wife and I decided to go to Montgomery to see the Equal Justice Initiative Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. We were familiar with Bryan Stevenson’s work, chronicled in his powerful book Just Mercy, and his mission to serve poor, black prisoners wrongly convicted of murder or subjected to excessive incarceration. Now, we wanted to see the National Memorial he’s created to honor the victims of lynching throughout the South.

I love to travel. A few years ago, sitting around a campfire, we played a game where we each listed all the states we had visited. I came up with a total of forty-three out of the fifty. Not bad, I thought. In accordance with our defined rules, this included some I had driven through on cross-country trips, perhaps stopping once for gas, or “seen” only in the sense of spending a layover at an airport. But all the states in which I had never even stepped foot lay in the South: Missouri, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, West Virginia, South Carolina, and Alabama.

I held all sorts of stereotyped notions about the South that kept it off my list of travel destinations. I assumed it would be hot and muggy, and full of greasy fried food, but mostly, inhospitable to someone like me: a far-left white lesbian from the San Francisco Bay Area who loathes the evangelical Christian right and the current President, and can’t understand how the two have embraced each other. But when we read about the National Memorial in Montgomery, we decided we needed to go. We called it our “Truth and Reconciliation” tour.

We flew into Atlanta, and spent the following morning at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. This museum (opened in 2014) is located downtown, near the Centennial Olympic Park, and provides a powerful experience. The interactive exhibits showcase the absurdities and injustices perpetuated under the Jim Crow laws, which prohibited racial mingling in all aspects of daily life: the well-known separate drinking fountains, of course, but also laws criminalizing black amateur baseball teams from playing within two blocks of a playground designated for whites, or the mixing of barber shop utensils between the races, or the transfer of school books between black and white kids. The captions read: Seriously?

On the day we visited, dozens of fresh-faced schoolchildren—5th or 6th graders, I guessed—both black and white, swarmed over the exhibits, notebooks in hand, gathering the answers to their assigned questions. Maybe they were too young or strictly forbidden to use cell phones, but I was struck by how focused they were, how earnest, as they examined exhibits about the death of the black girls in the Birmingham church bombing, or the “Little Rock Nine” being escorted into high school by the National Guard. In one exhibit, not recommended for children under the age of thirteen, visitors were invited to sit on a stool, place their hands on the “lunch counter”, don headphones, and see how long they could tolerate the simulated verbal and physical abuse of those protesting their presence. It was terrifying; the noise pummeled through my bones, the counter shook in an eruption of violence. I lasted only twenty-five seconds.

After a lunch at a diner where we had the privilege of not being harassed, we took a Lyft to the rental agency to pick up our car for the drive to Alabama. Our Lyft driver was a chatty, African American woman with big hair and long red fingernails. She brought up the new law which had just been passed in Georgia, another state racing to pass draconian anti-abortion bills in the hope of overturning Roe v. Wade. I can’t remember how she introduced the topic, but I was nervous; this might turn awkward. Maybe she was an avid, religious pro-lifer. Well, no. She told us with pride about her daughter, whom she had raised as a single mother, who had just graduated from college. One thing she didn’t have to worry about, she said, in a matter-of-fact tone, was her daughter needing an abortion—because she was “going the same-sex route.” She then made it clear she was pro-choice, having needed “a procedure” herself at one time. Okay, so my preconceptions were all wrong.

We drove the three hours to Montgomery, making a short stop at the Tuskegee Airmen historic site, where the first African American fighter pilots were trained during World War II. Then we checked into our bed and breakfast, and set off to explore downtown. First impressions: Southern fried chicken and fried green tomatoes are delicious; downtown Montgomery felt very cosmopolitan, hip, and integrated; everyone was super friendly; they really do say y’all all the time; and there is a nice riverside park. Everyone called us ma’am. I have no idea what assumptions they made about our relationship, but no one was the least bit hostile.

Back at the B&B, we met our fellow guests. Two of the couples were from the Bay Area, very close to where we live, which seemed an amazing coincidence at first. But then we realized all the patrons were white liberals like us, from the coastal “bubbles”, all in town for the same reason: to see the Peace and Justice Memorial. The presence of the Memorial and the Legacy Museum must be changing the face of tourism in the city.

The following morning, we went to the Memorial site under overcast skies, which set an appropriate tone. The site is spread over six grassy acres, dominated by the memorial structure at the center: a haunting shrine to the victims of the lynchings that took place between 1877 and 1950 in the United States, predominantly in the South. The Equal Justice Initiative has identified over 4,000 of these victims. Each county is represented by a large steel monument, six foot high, engraved with the name and the date of these terror attacks: “Wilkinson County, Mississippi: Charles Brown, 09.11.1879”. As you walk down through the structure, through the hundreds of rust-colored blocks—eight hundred in total—the path descends so that many of the blocks now hang above your head, eerily evoking images of black bodies hanging from trees. Some blocks contain two or three names; others a long list. Some counties have recorded victims only in the 19th century; others continued into the 1940’s. Some victims are anonymous, only the date known; sometimes multiple lynchings occurred on a single day.

The following morning, we went to the Memorial site under overcast skies, which set an appropriate tone. The site is spread over six grassy acres, dominated by the memorial structure at the center: a haunting shrine to the victims of the lynchings that took place between 1877 and 1950 in the United States, predominantly in the South. The Equal Justice Initiative has identified over 4,000 of these victims. Each county is represented by a large steel monument, six foot high, engraved with the name and the date of these terror attacks: “Wilkinson County, Mississippi: Charles Brown, 09.11.1879”. As you walk down through the structure, through the hundreds of rust-colored blocks—eight hundred in total—the path descends so that many of the blocks now hang above your head, eerily evoking images of black bodies hanging from trees. Some blocks contain two or three names; others a long list. Some counties have recorded victims only in the 19th century; others continued into the 1940’s. Some victims are anonymous, only the date known; sometimes multiple lynchings occurred on a single day.

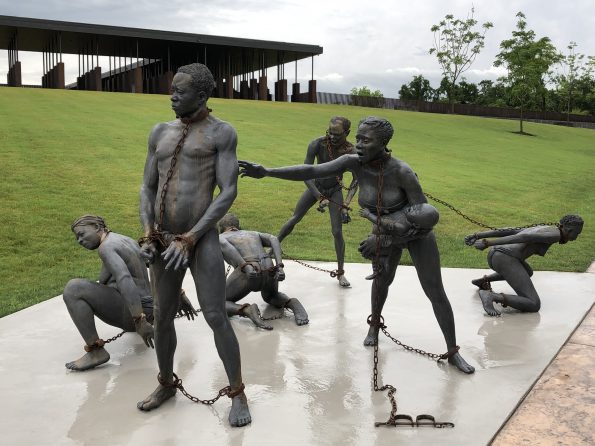

No one runs or laughs here. Near the entrance, a group of life-size sculptures show slaves in chains, families being torn apart; visitors are instructed to take no selfies around these statues. Outside the memorial structure itself, identical blocks representing each county are arranged horizontally on the ground in a field, resembling rows of coffins. The plan is to encourage counties to submit a request for their markers to be installed locally, in conjunction with public work towards truth telling and reconciliation in their communities. Eventually, those counties that fail to confront their history will be exposed here.

A plaque on the wall of the memorial reads:

For the hanged and the beaten

For the shot, drowned and burned

For the tortured, tormented and terrorized

For those abandoned by the rule of law.

We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice

With courage because peace requires bravery

With persistence because justice is a constant struggle

With faith because we will overcome.

I left feeling stunned, overwhelmed by a tightness in my chest. And we still had the Legacy Museum to visit. It’s located three-quarters of a mile away, in downtown itself, on the site of a former slave market. Our timed-entry tickets in hand, we walked into the first exhibit area to face haunting replicas of slave pens, with hologram images and verbal testimony of those awaiting their fate at auction. In an echo of the monuments at the Memorial site, another wall is covered with large Mason jars arranged on shelves, each containing soil—brown, red, gray, green, or yellow— collected by volunteers from the sites of identified lynchings, and labelled with the name, county, and date of death.

Other exhibits highlight the history of white supremacy, the violent opposition to integration, and the continued racial terrorism in this country, connecting the dots from slavery to lynching to codified segregation and now, in our own time, mass incarceration. It’s almost unbearable. I watched an older African American woman with a young boy about five years old, whom I took to be her grandson. They stood over a glass case with a video display chronicling how free blacks were forced into indentured service during Reconstruction, while from an opposite wall, archival footage of George Wallace bellowing “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” played on a continuous loop. The boy’s eyes barely reached the top of the case, but he waited patiently while his grandmother read intently, gently rubbing her hand across his closely-cropped hair. I wanted to wrap them both in my arms and weep.

When I’d mentioned to a writer friend that we were planning a trip to Montgomery, she told me she knew a woman from the Bay Area, recently retired, who had just relocated there, and she gave me her contact information. Jill said she would be delighted to meet for lunch. Still reeling from our visit to the museum, we met her downtown. She was wonderful and welcoming. She took us to the Civil Rights Memorial, created by Vietnam Memorial architect Maya Lin, to honor those who died fighting for civil rights in the 1950’s and 60’s; showed us the Inside Out project, where 4-foot high portraits of everyday residents are being erected on the side of downtown buildings; and drove us around the diverse neighborhoods.

It was fascinating to talk with her. She had moved to Alabama seven months earlier, with no family or other connections to the state. Partly, the relative property values allowed her to buy a pleasant three-bedroom house in a nice neighborhood, and still have money to fund her retirement. But also, she found a welcoming community. A gay couple lives across the street from her. And there is plenty for a progressive activist to do. She was protesting on the steps of the capitol the day the anti-abortion bill passed the House. She told us about the struggle to challenge racial gerrymandering in the state, and the huge obstacles to voting in the black rural areas: polling stations are sparse, there’s no early voting, and access to absentee ballots is strictly limited.

We later took the forty-mile drive to Selma to see the iconic Edmund Pettus bridge, the site of the infamous Bloody Sunday attack on civil rights marchers in 1965. There’s not much to see in Selma apart from the bridge itself, which crosses the main highway—so getting a photograph without traffic required some patience. On the other side of the bridge, in a small park by the river, a young African American man had set up a makeshift souvenir stand. A regular working class guy, he spoke with excitement about his involvement in the recent Senate race in Alabama, where Doug Jones had captured the seat for the Democrats, telling us about his role driving voters to the polls that day. He pointed to his grandfather, who had been on the historic march to Montgomery, now seated off to the side in the shade of a tree, waving at us with a broad grin. We passed on the tacky t-shirts and mugs, but gave him $20 for a poster of the fiftieth anniversary walk across the bridge led by President Obama.

Our planned itinerary called for us to leave Alabama the following morning, off on a road trip to Asheville in North Carolina and then down to Charleston, South Carolina. We would enjoy both places—but felt ripped from Montgomery too soon. There was so much else we didn’t get to see. We had no interest in any of the Confederate sites or monuments, such as Jefferson Davis’ “First White House of the Confederacy”, and didn’t want to visit historic plantations built on the backs of slaves. But we would have liked to have seen the Rosa Parks and the Freedom Rides Museums, as well as the Dexter Parsonage Museum, on the site where Dr. Martin Luther King lived in the late 1950’s—all located in downtown Montgomery. And I’d like to visit Birmingham and Monroeville too. There’s much to come back for.

Jill and I became friends, and I have been following her on social media ever since. Two days after we left Alabama, she was back at the capitol when the bill came up in the Senate, with a large group of women and men, black and white, many dressed in red Handmaids Tale cloaks, raising their voices for women’s reproductive freedom. But more than that: she’s on the front line every week acting as escort at Montgomery’s only abortion clinic. She and other brave women and men don rainbow-colored vests and carry huge umbrellas to shield the women entering the clinic from the barrage of abuse from the harassers; they cover the clients’ license plates so they can’t be traced. Those protestors are a scary bunch. In the safety of my California bubble, I’m not often called upon to display such courage.

When Jill posted photos of the abortion clinic action, a man who happens to be an acquaintance of mine responded immediately with a “Boycott Alabama!” comment. Really? What sort of response is this from the safety and comfort of a home in the Berkeley hills?

I understand that boycotts can be effective. I remember the grape boycott and the boycott of all things South African in the era of apartheid. Sometimes, a boycott feels like the moral imperative; I will never shop at Hobby Lobby, for example, because of its ultra-conservative politics. But I’m grateful for what Jill and her progressive friends are doing, and I want to give them all the support I can. I don’t think I could live in Alabama myself—I enjoy my liberal haven too much. But if all progressives run from the Red States, nothing will ever change.

As we left the Legacy Museum in Montgomery on the day of our visit, I clasped my hands over my heart and nodded silently to the young African American woman staffing the entrance. “Thank you for coming,” she said—a rote comment, perhaps, along the lines of “Have a nice day.” But I thought, Oh, my God, this is the least I can do. How can we ever make amends? What can we do? Recognize our white privilege: absolutely. Call out racism whenever we see it: sure. And support calls for restorative justice: public investment in schools, transportation, technical training sites, infrastructure in black communities, and enforcement of voting rights. It’s a long, overwhelming list.

For now, I have donated to the Yellowhammer Fund which helps women in Alabama overcome barriers to abortion access. We downloaded and listened to Bryan Stevenson’s audiobook of Just Mercy, as we drove through the Carolinas, feeling inspired to give generously to the Equal Justice Initiative in honor of their amazing work. I look forward to my next visit to Alabama, and in the meantime, I’ll continue to offer my support.

![]()

Barbara Ridley

Barbara Ridley lives in the SF Bay Area. After a career as a nurse practitioner, she is now focused on creative writing. Her debut novel When It’s Over (She Writes Press, 2017) is based on her mother’s story as a refugee from the Holocaust, and won 6 Finalist Awards. Find her at barbararidley.com

Alice Feller - September 10, 2019 @ 8:05 pm

This is a beautifully written and moving essay. Wonderful showing of the contradictions and the surprise of Alabama. And the picture is amazing.

Ginny Kamp - September 10, 2019 @ 5:45 pm

Dear Barbara,

Thank you for opening my eyes to the struggles and joys in “Sweet Alabama.” I am so moved to visit myself now.

Robert Pizzi - September 8, 2019 @ 6:59 pm

Dear Barbara,

I am very moved. I think your challenge to what I refer to as “geographic determinism” is really right on the mark. There are wonderful progressive people everywhere and our hope must be that we can support them/us to finally have a solution to the regressive policies that are being peddled by a desperate, waning, “false, paper tiger” right wing. Keep the spirit and faith. Bob