Back in the Saddle

By Barbara Ridley

I come home exhausted, good for nothing except collapsing onto the couch and spacing out, barely able to absorb the TV news. My dear wife hands me a glass of wine and returns to the kitchen to prepare dinner. After eating and briefly catching up on my email, I’m ready for an early night. I can’t imagine returning the next morning, up at dawn for another 9-hour shift, but thankfully, I don’t have to. I have a week to recover.

I don’t know how I ever did this full time. But at one day a week, I’m loving it. For the past three months, I’ve worked as a volunteer at a COVID-19 mass vaccination site. I’ve kept my nursing license active since retiring five years ago, so after a year on the sidelines, watching in despair as healthcare workers from Italy to New York to Los Angeles dealt with unfathomable challenges on the frontlines, I can now at last make a small contribution in the fight against the pandemic.

I don’t know how I ever did this full time. But at one day a week, I’m loving it. For the past three months, I’ve worked as a volunteer at a COVID-19 mass vaccination site. I’ve kept my nursing license active since retiring five years ago, so after a year on the sidelines, watching in despair as healthcare workers from Italy to New York to Los Angeles dealt with unfathomable challenges on the frontlines, I can now at last make a small contribution in the fight against the pandemic.

It took some effort to find a way in. I realized in early January that immunizing a nation of 330 million would be an extraordinary endeavor, and I searched everywhere for opportunities to volunteer. I emailed the public health department in two counties and one city and contacted three community clinics—but heard nothing for weeks. Finally, I was invited to upload a copy of my license (of course,) submit to a background check (sure,) do an online HIPPA privacy training (whatever,) and then drive to the sheriff’s office at the other end of the county to stand in a parking lot and swear an oath of allegiance to the constitution of the United States, and another to the constitution of the State of California (really?) I passed muster on all counts and was cleared to go.

On my first shift, I certainly felt rusty. As a nurse practitioner, I performed invasive procedures for years, but not simple injections, and I was unfamiliar with the advances in needle technology. The site where I first volunteered, a mass drive-through center sponsored by the city fire department, provided a smooth, convenient experience for the public, but was disorganized from a volunteer perspective. I was told to briefly observe another volunteer nurse, who was younger than I but also evidently unfamiliar with the new retractable needles, and then launched on my own, and moved from one station to the next as relief for those on break. I didn’t harm any patients, but it was several hours before an LVN showed me how to correctly dispose of the needle after use.

I also found it challenging to vaccinate people sitting in cars. Everyone else seemed to manage effortlessly, but I fumbled trying to hold syringe, alcohol wipe, gauze swab, and Band-Aid, then stabilize the deltoid muscle and inject, all with only two hands, using my knee to prop open the car door, and my elbow to brush away the paper gown blowing into my face as the wind barreled across the parking lot.

I also found it challenging to vaccinate people sitting in cars. Everyone else seemed to manage effortlessly, but I fumbled trying to hold syringe, alcohol wipe, gauze swab, and Band-Aid, then stabilize the deltoid muscle and inject, all with only two hands, using my knee to prop open the car door, and my elbow to brush away the paper gown blowing into my face as the wind barreled across the parking lot.

After three weeks, that site stopped accepting volunteers and I was redirected to another in East Oakland, in a predominantly Latinx and Asian immigrant community, and I’ve been there ever since. It’s extremely well organized by an amazing group of county public health nurses who make sure all the vaccinators are oriented to the syringes in use each day. County employees function as support staff doing registration, data entry, and controlling the flow, while most of my fellow vaccinators are volunteers: a retired dentist, a dermatologist, a city college nursing professor, and some actively employed healthcare professionals volunteering on their days off.

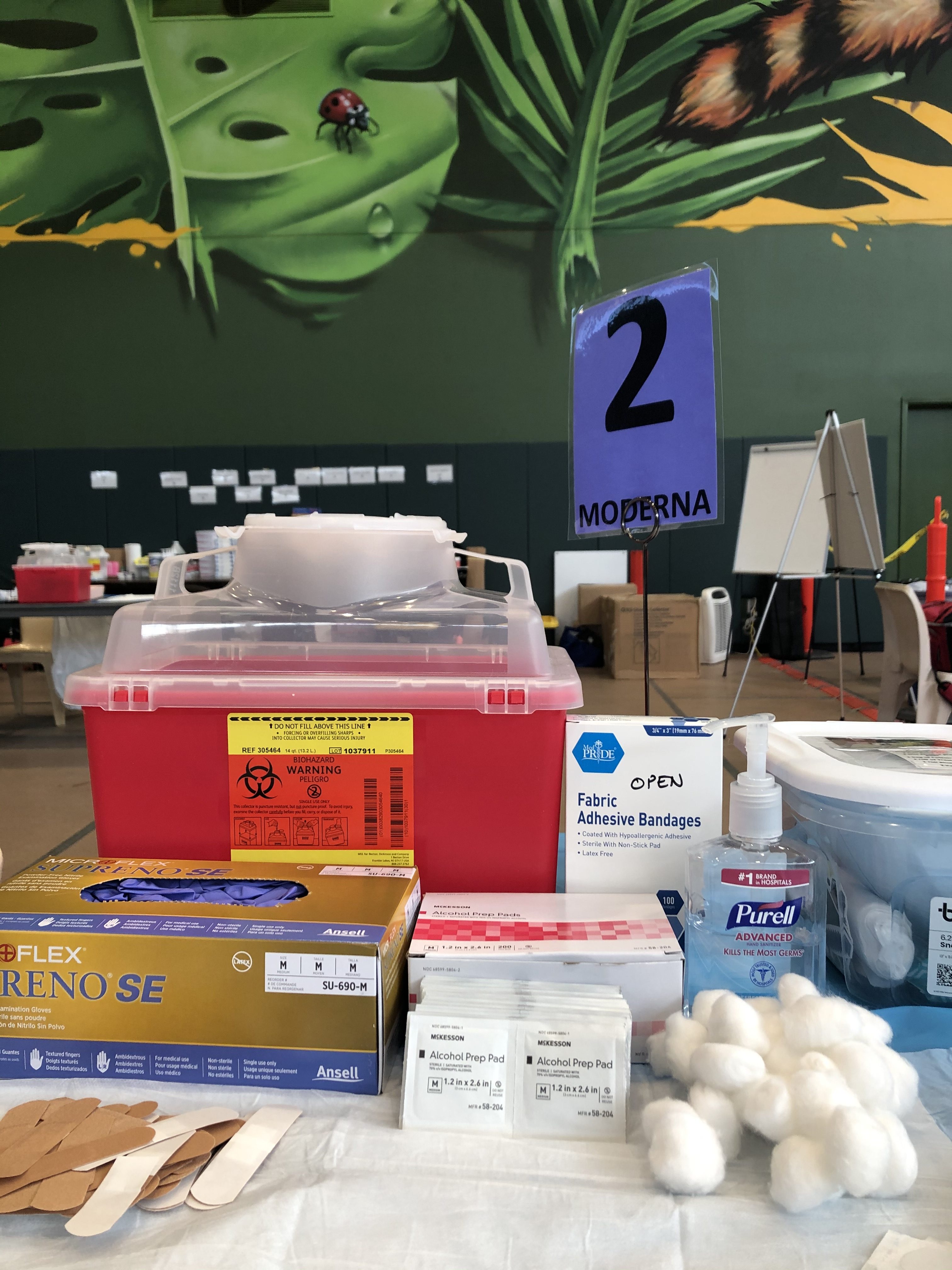

I love this site because it is well organized, but also because of its mission to serve the surrounding zip codes which have been so heavily impacted by the pandemic. One quarter of the doses each day are reserved for walk-ins, people who lack internet access to make appointments; they arrive clutching flyers printed in four languages and distributed in the neighborhood. And I like being situated in a high school gym, where I set up my own station on a table in front of me, no sun or wind in my face. I’ve become proficient and fast, injecting up to 130 people a day.

But most of all, I’m reminded of why I love nursing. As a child, I never dreamt of being a nurse; no one in my family was in healthcare, and some of the adults in my life (although not my parents) despised occupations such as nursing or teaching for being insufficiently intellectual. But a few years after graduating with a suitably academic but useless degree, I chose to train as a nurse and do something practical.

I always harbored a vague fantasy of—oh, I don’t know—going to Mozambique to help cure malaria or something, but that never happened. I worked long and hard for forty years, predominantly with patients who were poor or disadvantaged or disabled, before happily retiring to pursue writing and other interests. Now, in the worst healthcare crisis of my lifetime, my Mozambique moment has arrived.

I apply another dab of hand sanitizer and wave to the young man controlling the line to indicate I’m ready for my next patient. A middle-aged Latina woman takes a seat next to me at Station Number 2, handing her ID to my “vac support” person on the laptop to my right. I smile behind my tight-fitting N95 mask and tell her I’m so glad she’s here. As I don a pair of purple nitrile gloves, I ask if she’s ever had a severe reaction to any medication or injection. This question is already addressed on the screening form, but I need to check again whether she should be designated for additional monitoring after the shot, and it allows me to gauge whether I need an interpreter to explain the importance of the second dose or how to manage potential side effects. Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Vietnamese interpreters roam the room, identified by their bright yellow vests. But this woman speaks perfect English, so we’re good to go.

I can tell she’s nervous. She clutches a Kleenex, and winces as I unwrap a Band-Aid and alcohol wipe. I stroke her arm, asking her to raise her sleeve, encouraging her to relax, telling her I’ll be as gentle as possible. I tuck the short sleeve of her blouse under her bra strap to keep it in position above the smooth brown skin of her upper arm. She’s a large woman. The three remaining syringes at my workstation all have the regular, short needle; I should use the longer needle on her, to make sure I inject into muscle and not subcutaneous tissue. I glance over to the table at the front of the room, fifteen feet away, where the public health nurses reconstitute the vaccine and prepare the syringes. One catches my eye and I raise a finger, and she immediately understands my need; she wordlessly approaches and drops a long-needle syringe at my station.

can tell she’s nervous. She clutches a Kleenex, and winces as I unwrap a Band-Aid and alcohol wipe. I stroke her arm, asking her to raise her sleeve, encouraging her to relax, telling her I’ll be as gentle as possible. I tuck the short sleeve of her blouse under her bra strap to keep it in position above the smooth brown skin of her upper arm. She’s a large woman. The three remaining syringes at my workstation all have the regular, short needle; I should use the longer needle on her, to make sure I inject into muscle and not subcutaneous tissue. I glance over to the table at the front of the room, fifteen feet away, where the public health nurses reconstitute the vaccine and prepare the syringes. One catches my eye and I raise a finger, and she immediately understands my need; she wordlessly approaches and drops a long-needle syringe at my station.

I administer the vaccine and apply the Band-Aid. My patient takes her vaccination card, and I point out the appointment for her second dose. She thanks me over and over, dabbing at tears streaming down her cheeks. Then she tells me: three of her family members died from COVID. I place my hand over my own heart and say how sorry I am for her loss.

This is where I need to be. I’m back in the saddle and there’s nothing rusty about my most important nursing skill: being with her in this moment.

And then I pivot. As nurses do. I cheer with the next guy who pumps his fist in excitement, laugh with the gal who’s brought in her own psychedelic-colored Band-Aid, reassure the man who wants to know if he can eat regular food tonight, and the young woman who asks if the vaccine will affect her fertility.

The vaccination site is housed in a gleaming, brand-new gym that the students have not yet seen, because the school has been closed all year. One day, I vaccinated an eighteen-year- old, a senior at the school, who gazed up in wonder at the new facility, lamenting that she never got to use it. Two of the walls are decorated with a spectacular mural, sprawled above the basketball hoops and behind the scoreboard, depicting a tiger—the school’s team mascot—in a jungle of leaves and butterflies and lady bugs.

The vaccination site is housed in a gleaming, brand-new gym that the students have not yet seen, because the school has been closed all year. One day, I vaccinated an eighteen-year- old, a senior at the school, who gazed up in wonder at the new facility, lamenting that she never got to use it. Two of the walls are decorated with a spectacular mural, sprawled above the basketball hoops and behind the scoreboard, depicting a tiger—the school’s team mascot—in a jungle of leaves and butterflies and lady bugs.

Recently, the flow of people has slowed to half of what it was initially, reflecting reports from elsewhere in the state and the nation, that mass vaccination sites have perhaps reached a saturation point in terms of those who are willing and able to attend. Focus will soon shift, I think, to smaller, more mobile operations that can find people wherever they are. I hope there will be a role for me in this next stage.

For now, as I wait for the next person to take a seat beside me, I give a nod to the tiger on the wall, and think: yup, we’ve got this.

![]()

Barbara Ridley

Barbara Ridley lives in the SF Bay Area. After a career as a nurse practitioner, she is now focused on creative writing. Her work has appeared in The Forge Literary Magazine, Ars Medica, The Copperfield Review, Blood and Thunder and Stoneboat, among other places, and her debut novel, When It’s Over (She Writes Press, 2017) based on her mother’s story as a refugee from the Holocaust, won 6 Finalist Awards. Find her at barbararidley.com

Marlene - July 23, 2021 @ 7:21 am

Simply? I am humbled. Thank you for doing human so very well.

Cheryl Suchors - July 22, 2021 @ 9:18 am

Grateful that you worked hard to be able to join the effort combating this disease … grateful as well that you are still writing! Cheryl

Carl - July 21, 2021 @ 10:49 am

What an informative and personal piece of reporting. You are one of many heroes of these pandemic times. And an absorbing writer to boot.

Thank you!

Ginny Kamp - July 20, 2021 @ 9:50 pm

I love it. Ginny

Sue Granzella - July 20, 2021 @ 7:21 pm

Oh my goodness, Barbara, this is wonderful!!! I inhaled this piece; it’s fascinating and important and inspiring to read a bit about what it is/was like getting the vaccinations out. I teared up as soon as I reached the part where you began telling the story of the Latinx woman. This pandemic has united all of us, even when we don’t realize that. I loved learning a bit about others’ experience of it. Thank you for this piece, and thank you for your efforts!!

Michelle Burrill. RN CCM - July 20, 2021 @ 3:00 pm

LOVE THIS -me too an RN retiree lucky enough to be back in the saddle /vaccinating- so well written BARBARA -so easy to feel your words -THANKS