From Son: Birth of the Poet

By Sharon Doubiago

Thursday, October 17, 1974, Greenwood Pier Café, Elk

“Towards end of the month a unique encounter.” Taurus forecast for October 1974.

At the beginning of the month a psychedelic 8 ½ by 11 hand-painted and ink poster on the redwood post of the Little River Market: OPEN POETRY READING, The Greenwood Pier Cafe, Elk, 7 P.M.

I fought the entire two weeks against having a heart attack, tricks against fear I learned in the second grade. I went into severe identity crisis, knowing again every reason I’d ever come up with not to be a poet. Every night my dreams were of bizarre murders, the sound of bullets entering me, strangulations, dismemberments, decapitations. It was if all time, the past and future, was bearing down to this one moment—maybe ten minutes. I wouldn’t let anyone know I’d never read before. I couldn’t be that vulnerable. It was now or never. It’s set. I’m a poet, I will read.

Just before I read, a woman named Loretta Manill reads a poem of the acclaimed poet Anne Sexton as she commits suicide. Loretta will become of profound importance to me, like a foundation, a root, a model for being a poet. She writes as a woman. I’d never encountered a female poet in my college and post-college studies. Thirteen days before, on October 4, Anne Sexton is sliding down the front seat of her car, dying of carbon monoxide. Loretta’s poem slowly becomes the consoling mother’s voice, “it’ll be alright, darling.” A particular horror of Anne Sexton’s suicide was what seemed the literary world’s waiting for it. She had predicted it herself in verse, she’d kill herself as her friend the poet Sylvia Plath had killed herself. There had been a review by an influential male literary critic of Sexton’s work a few weeks before her death, criticizing her for being sexually provocative in her poetry, a charge of which I’m terrified, that the long-subdued rhythm of my body will be deduced as sexual, as seductive. In many ways—tone, technique, subject, wounds—I recognize my sister, Loretta Manill. From her I can learn to write like a woman. From her I have permission.

My journal notes were always trying to become poems, but to manipulate them from the raw material felt dishonest. I worked to keep them from becoming poems. But since moving to Mendocino six weeks before, I’d been allowing the notes to shape into little things.

The first poem I read to an audience (of poets no less!) is my necessary manifesto, “Against Metaphor.” I will not use language to lie, to exploit one thing for another.

“Poets whose tool is metaphor

armies whose weapon is betrayal of the dream

loggers who don’t see the tree. I want to write

poems as the tree growing

l want the tree to grow me

not me the tree.

I want to see.”

Then I read “Godiva,” about the father’s sexual betrayal of the daughter. I was called Lady Godiva as a little girl by my father. I’m so nervous, my voice so wobbly up and across the rapids of my breath, sometimes large gasps without breath or words, just sucking voids, other times rushing out on gasps without stops, a voice trying to defend itself, the little girl accused of traipsing nude to titillate Daddy and our company, my beleaguered and badgered body beginning to rock back and forth to create a self-protective energy shield to say the poem, a shield from their penetrating, damming eyes. Being called Lady Godiva is my earliest memory of being accused of something I’m innocent of. My earliest memory of a broken heart. My earliest memory of my father’s terrifying self-titillation. My self damned for being titillating.

My third poem is “Vaginal Envy,” the vagina likened to

“the giant virgin redwood stumps

their burnt-out hollows everywhere on the land, flashes

of a recurring nightmare

I can’t remember.”

Metaphors! I’ve sold out already!

Mark is in the audience. To embarrass the most private of men who nonetheless has encouraged me to write, the man I love with all my heart, body and soul, oh, that I don’t fall on my knees before him this night, beg for his understanding and forgiveness.

I’ve always said it was the murderous lying words that led to the Vietnam War that caused me to vow never to be a poet. I will spend the rest of my life as a poet digging up the roots of that war, all wars, and my own war against my true vocation.

Nothing will ever be the same.

Poets who read this night who, along with Loretta Manill, will be my guides for the rest of my life are Bill Bradd, Gordon Black, Carl Kopman, Luke Breit, Peter Lit, Lydia Rand (Riantee now), Don Shanley, Pauline Katz (later Kiva, later Rasunah, finally Katz), and Curt Berry (who will die of Agent Orange. He’s in hiding on the Mendocino Coast until he and other Vietnam deserters are pardoned.)

——–

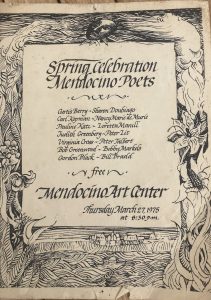

Thursday, March 27, 1975, Mendocino

On my mother’s 55th birthday she and my father buy a lot in Florence Oregon which in time will become the place of their permanent home. Unlike my usual reclusive side I’ve continued since last October participating in the monthly open readings in Elk, and now I’ve actually organized and will host a Spring Celebration Poetry Reading at the Mendocino Art Center. I feel a joy I’ve never known. But for these five months, approaching the event, I also feel an inexplicable, foreboding dread: a deep sadness. Something dark, negative. Fear, greater than usual. Years from now I’ll realize that the dread and sorrow of becoming a poet, why it took me so long to become one—most poets testify their poems began in childhood—was that writing poems would inevitably lead me to the suppressed memory of my father’s rape of me at seven. I remembered the ongoing “lesser” violations and “forgave” him, as I learned I must do in Sunday School to save my soul. And his. I did not remember the rape.

Fundamental for me is having found a community that respects and celebrates many different aesthetics and outlaw voices, including my own. The beauty here, the wild ocean, the giant redwoods, demand an honesty that make a single poetry aesthetic, as with almost all “schools,” absurd. Fascistic. The wild, breathtaking demand of the Mendocino coast, the soul ache, is for truth. In protection of the truth I’ve hidden it, but I have not lost it. Nor my soul. Nor his.

But how will this affect you and your sister, your love for your grandfather?

![]()

1 Son is a book length manuscript, nearing completion, addressed to my son.

Sharon Doubiago

Sharon Doubiago is a San Francisco poet and memoirist of many books.

Poetry: Hard Country (epic poem, West End Press), South America Mi Hija (book-length poem, U of Pittsburgh Press), Psyche Drives the Coast (Oregon Book Award for Poetry. Empty Bowl Press), Body and Soul (Cedar Hill Press), Love On the Streets (U of Pitts), The Visit (50 page poem, Wild Ocean Press), and most recently Naked To The Earth (poetry, Wild Ocean Press)

Memoir/Memoir stories: The Book of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (Greywolf), El Nino (Lost Roads), My Father’s Love, vol 1 +2 (Wild Ocean) and My Beard, Spuyten Duvyil

SharonDoubiago.com

Michael Smith - August 28, 2022 @ 12:40 pm

Never easy to show what we wish to protect and hide–our secret treasure.

You are a courageous soul.

Dan - August 26, 2022 @ 10:32 am

Nicely done. I enjoyed this.