Coming of Age at Adams-Mahoney

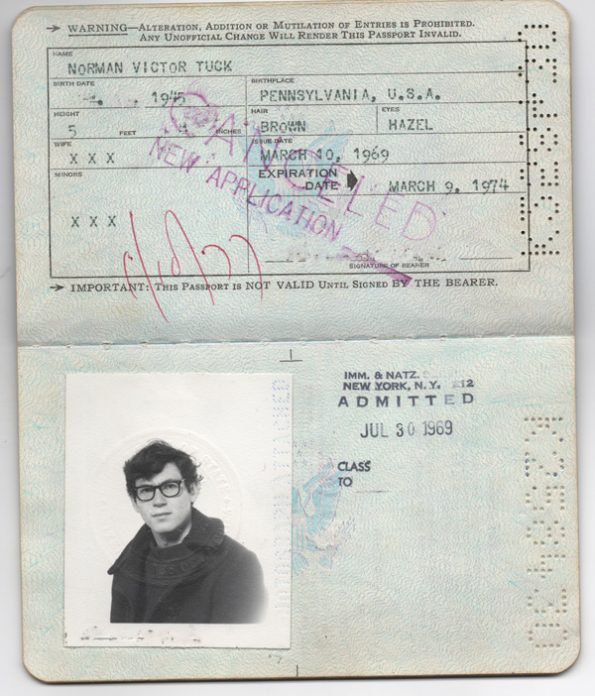

By Norman Tuck

I was 22 when I left Florida for New York. It was September of 1967. I fit my tools and my clothes into an MGB to follow Interstate 95 north and then east through the Holland Tunnel toward a new life.

In the Yellow Pages I found “Adams-Mahoney and Company,” a British-Leyland repair shop at East 74th St. on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. I showed up and was told to bring my toolbox on Monday to start working.

That night I parked the MG in front of Emmanuel Turk’s real estate office on East 14th Street. I slept as best I could in a bucket seat, hidden from the street beneath the MG’s black tonneau cover.

In the morning I was first in line to see Mr. Turk. He was an orthodox Jew who had been filling the Lower East Side with a new breed of out of town kids, like me.

By evening I was hauling all that I owned up the three flights of stairs to Apt. 4E, 32 East 1st Street. I’d been given a two-year lease at $75 a month. My new home was six blocks south of the Fillmore East and one block west of Katz’s Delicatessen. I was, suddenly, a New Yorker.

*****

Weekday mornings saw a 74 block run up First Avenue. Synchronized lighting, top down and fast.

I should have clocked in by 8. But, I was always late, until George told me that they “would raise me to $100 a week” if I showed up on time. After that I was usually punctual.

Monday mornings started with the shop nearly empty. Just a few dust covered older exotics that sat waiting for parts. Then the cars started coming in. Mostly MGBs, with a smattering of Healeys, Midgets and a few other British orphans.

The cars were the swan song of the British industrial revolution. Their maker, British Leyland, was a conglomerate of dying British corporations that had huddled together in a last hope for survival. The little sports cars were simple, elegant machines, but their design had never really made the transition to modernity. Still, for me, they glowed with a beauty that transformed the darkness of the dingy shop where I had come to work.

The shop and the work were probably not much different from the earliest days of automotive history. There were no hydraulic lifts and no pneumatic tools. Problem cars went to more experienced mechanics, making my workday was very, very routine. Most of the cars were fairly new MGBs, with which I had great familiarity, and I would usually perform small repairs and periodic maintenance.

Lube Oil and Filter

I would go to George’s desk in the office and pick up a work order with the car’s description (White MGB), license number, and an instruction; usually “Lube oil and filter.” I’d find the car, open its hood and press the fan belt to check its tension.

I would get in the car, take it out of gear, set the handbrake and turn the key to start the engine. With the engine running, I would determine its general state of tune by first listening to its idle, then jabbing the throttle to see how quickly the engine reacted.

Back in the car, turn off the engine, out of the car, roll a jack under the car, jack it up, lower onto a set of steel horses, remove the jack. Slide a big tin drain pan under the engine, lie down on a wooden creeper, roll under the car, unscrew the drain plug and oil filter canister. I always enjoyed watching the thick, black liquid flow from the engine into waiting drain pan, below.

After the dripping stopped I carefully threaded the little drain plug in place at the bottom of the engine before tightening it with my trusty box wrench. The drain pan was heavy with used oil as I carried it to the oil drum at the front of the shop to empty it through a big funnel into the drum.

I threw the used fabric oil filter into a trash can and took the red metal filter canister to a tub of pungent kerosene and wiped it clean with a red rag. I got a fluffy new, white, cotton filter from the parts room and placed it into the filter canister.

Sometimes the rubber “O” ring that sealed the canister would become hard, in which case it had to be replaced. This was a tricky job that required laying under the car, using an ice-pick to remove the old “O” ring and then delicately pressing a new, skinny black “O” ring into its narrow groove. With that done, I would finally bolt the canister back in place on the engine.

By then I was more than ready to get out from under the car and take a little walk to the big drum of fresh Castrol 10-30 that resided near the shop entrance. The drum had a pump with a handle that I would crank to pump 5 quarts of oil into a tin pitcher which had a flexible, metal spout. I’d carry the full pitcher back to the car and the empty clean, fresh oil into the engine. I would then start the engine and quickly look under the car to see if I did my job well and that there was no oil surging onto the floor.

Back onto the creeper and under the car with a grease gun to look for leaks at the gearbox and rear axle, and to pump black grease into fittings on the tie rods, kingpins, drive shaft, and emergency brake cable. Toss dry absorbent onto spilled oil (“feeding the chickens”), jack up the car, remove the horses and lower the car back onto the ground.

Top-up the engine, brake, clutch, radiator and SU carburetor fluids before closing the hood, initialing the service order, and writing down any residual problems that I may have observed.

A walk to the office to hand in the completed work order and pick up a new work order, usually; “Lube oil and filter.”

Tires and Wheels

In late Fall I’d mount snow tires onto heavy wire wheels. Come Spring I’d replace the snows with fast Dunlops, which I mounted onto the car and then balanced.

The balancing machine had a powerful electric motor that spun the front wheels at high speed. I’d carefully place a sensor on the car’s suspension. The sensor triggered a strobe light aimed at the spinning wheel. The strobe light magically made the wheel appear to be standing still, with the heaviest area at the bottom. I would stop the spinning wheel and hammer lead weights onto the rim at proper positions on the rim. The process would be repeated until the wheel spun smoothly, without vibration. It required two mechanics to balance the driving wheels, one to balance the wheel and the other to sit in the driver’s seat of the raised car and rev the engine until the speedometer showed sixty miles per hour.

It was thrilling and a little scary to work just inches away from a heavy wire wheel spinning at highway speeds. As a teenager in Miami I had watched this process being done to my father’s car. I think it was then that I decided that, more than anything else, I wanted to be a mechanic in a sports car shop.

A Healey Exhaust

Sometimes it would be my job to replace the exhaust system of a Big Austin Healey. I would crawl under the car with a flaming acetylene torch to remove the rusty pieces and then weld together a new assembly of heavy steel pipes, silencers, resonators, U-bolts and rubber hangers. It was a big job made harder when the tip of the torch got too close to a pipe and exploded with a loud “pop,” shooting sparks at my goggled face.

****

In the summer the shop floor was unbearably hot. We were issued light, cotton uniforms, and salt tablets were available near the water fountain. Big electric pedestal fans blew hot air in through the shop door and the few wire-glazed windows on the second floor, but nothing helped when idling engines filled the air with hot exhaust.

It was the New York City winters that I remember most. The shop was largely unheated. Our elegant black and gold woolen winter uniforms looked terrific, but they couldn’t keep away the cold. I could see my foggy breath as my naked fingers worked on cold metal.

A Test Drive

In good weather I might decide that a Big Healey or Mini Cooper S needed a test drive. I drove fast through traffic to enter the FDR Drive at 79th Street and then sped even faster to the exit at 63rd Street. It was a short but exhilarating circuit that would raise my spirits until the next oil change.

A Pre-Delivery Inspection

I had to do PDI’s, the Pre-Delivery inspections. Brand new MGBs and MGCs arrived from the docks in New Jersey. The cars came covered with a thick, dull wax. It took hours to wipe a car down with rags and kerosene and then prepare it for delivery. Later, I would park the gleaming car at the curb and watch it get picked up for a first drive by a happy new owner, usually a well-clad business man, or an excited, young daughter. By the late 1960s the MGs were so heavily laden with safety devices and emissions controls that I was not really proud of the car that I had prepared for delivery. The glory days of the British Roadster were over.

Coffee Time

At the shop I was considered “the kid,” and it was my job to deliver snacks at coffee time. At 10 and 3 I’d walk the shop floor and office announcing “coffee time.” I collected money and wrote orders in pencil on a little piece of scrap paper.

The choices were: coffee; light and sweet, dark, dark no sugar, or, of course, regular (milk and sugar). Some asked for tea with the same possible combinations. Most ordered either a “butter roll” or an “egg on a roll.” The butter roll was a seeded hard roll with a big glob of sweet butter tucked deep within.

I’d walk the few blocks to the Deli and stand in line to wait my turn with the other young gophers. I’d call my order to the counter man then move along to pay the nice lady at the register. I’d collect the brown bags and carry them back to the shop. Like the food, the constant banter of the Deli was warm and indigenous to New York at the time. “One regular,” was coffee without pretense.

I liked taking the orders. I liked the little walk. I liked the people in the Deli. But, most of all, I liked the 15 minutes when we mechanics sat together, exchanging stories before returning to the isolation of the work.

*****

Everyone at Adams-Mahoney shared an intense love for the automobile. We were “car guys” with a passion that I cannot explain. In childhood we had explored curious mechanisms by taking them apart. We tried to fix broken things. We sought speed and thrill-rode bicycles faster and faster toward the inevitable crash. Car lust had brought us together here to earn a living among those little British sports cars.

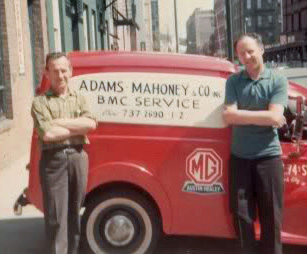

George Adams and Larry Mahoney were our bosses. George and Larry had individual strengths that functioned well together. They had worked side by side as mechanics at J.S. Inskip Motors.

Inskip had been a prestigious Manhattan importer of exotic automobiles since the 1930’s. It had provided custom Rolls-Royces and Bentleys to the moneyed elite. Eventually, Inskip dissolved in 1967, and George and Larry joined together to form Adams-Mahoney & Co. Inc. I suspect that they had received financing from the serious men in long wool coats that occasionally arrived in black Cadillacs for long meetings in the back office.

George had organizational skills, a clear mind, and a vast automotive knowledge. He was a good boss who was always honest and straightforward with me and the other mechanics. He kept the books and steered Adams-Mahoney on an orderly path. George had been a front line soldier in World War II, and he brought a post-war American optimism with him into the work place.

On weekends George and his teenage son raced powerful American dragsters on strips in New Jersey. He had little respect for the British two-seaters that were our bread and butter. In early morning and at closing time George’s modified, black on black Mustang shook the shop with a deep V-8 rumble that made the little British cars around it seem like toys from a lesser world.

Larry Mahoney. Customer relations were Larry’s domain. He was a charismatic entertainer who would schmooze the employees and the clients, making the office a fun place to be.

No customer escaped Larry’s Irish charm. I wouldn’t want Larry to fix my car, but I always enjoyed watching him do what he did best. I grew to like the warm smell of Larry’s whisky breath as he kept up a constant chatter of good cheer. As the day wore on he would become ever more ebullient with each drink, until, at days end, he would choose the classiest customer car to take home for an extended “test drive.”

*****

We mechanics were a rag-tag mix. Mike, Emelio and Marcel were three older Europeans who had worked together at J.S. Inskip before moving on to Adams Mahoney. Roy, Zion and Leroy were three young black men from Jamaica. Then there was me, a young man from Florida who enjoyed working on British cars.

Mike was a heavy-set Irishman who reminded everyone of Jackie Gleason, whom he would often expertly impersonate. He had worked with Larry and George at Inskip, and joined them to become shop foreman, parts man, and third in command. Part of his job was to drive the little red and white Morris panel truck to the parts depot in New Jersey and return to refill the shelves with needed supplies. He would hand out items as needed and work on the major, extended mechanical rebuilds that were always around.

I never really liked Mike. He lied about the most mundane things, making work difficult for those of us who depended on him. He seemed to have his own agenda that I did not understand. Although we seemingly got along, he was someone that I could have easily done without.

Marcelle was Belgian and a devoted Catholic. He was a very skilled mechanic who had worked with the others at J.S Inskip.

Marcelle with cap.

Marcelle attended morning Mass each day before coming to work in the very early morning. I never came early enough to see him arrive, nor stayed late enough to see him leave. He was probably in his late 50’s, and would occasionally mention his experiences as a long term prisoner in a Nazi P.O.W. camp. The camp had a lasting effect on his health, making him seem older than his years. Miraculously, he found the love of his life and got married during my stay at A-M. His loving wife, Maria, was his glorious reward here on Earth. Marcell was a good man and, as our best mechanic, was given the most difficult, technical jobs. I grew to love him and I miss him now as I write this.

Emilio. I also grew to love Emilio, though I felt sorry for him. He had been a soldier in the Italian Army, and, like Marcelle, World War II had not been good to him. Even though he was very experienced, having with the others at Inskip, he would often make mistakes and could no longer be trusted to do bigger jobs.

Emelio could display a violent temper, and the Jamaican mechanics would taunt him just to see what he would do. I can’t forget the time he threw a heavy iron shock absorber at one of them, missing the mark but leaving a lasting gash on the concrete wall behind the target.

Mamille, as Marcelle called Emillio, was probably too unhealthy to be working in our harsh conditions, and this added to his general unhappiness. High blood pressure made him dizzy, and his utterance; “Head no good today,” has stayed with me, especially now that I have shared the symptom.

Roy was the oldest of the three Jamaicans. He was a family man who had come to New York to better his situation. He kept a low profile, working hard without complaint. He sent most of his paycheck to his wife and family on “The Island.”

Every evening, after work, Roy attended class at night school to study computer science. His reasons for coming to New York were clear: it offered a “Land of Opportunity” where he could earn good money and receive an education that would insure a bright future for him, his wife and his children after he returned home.

Leroy and Zion were a couple of fun loving young guys on the make in the Big City. At lunchtime I would take in their stories of weekend parties and the girls that they had met.

There was much about their lives in New York that they did not like. Leroy and Zion reminisced about the tropical world they had left behind as we sat together, eating our lunches in a cold repair shop, watching falling snow through dirty, frosty windows.

As I listened to them reminisce about the Island, I wondered what it was that kept them in The City. With my limited background, I was unable to accept that it was only money that motivated them to leave Jamaica and endure New York, and I wondered if, like me, there was something more elusive that was keeping them here.

Eventually, the redundancy of the work made my days at Adams-Mahoney no longer fun. I never had it in me to become a real professional. I felt like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice: as I fixed one car, two others were breaking down somewhere else, and it was all too much for me. I’d had enough.

I was 25 when I left New York for graduate school in Pennsylvania. It was September of 1970. I fit my tools and my clothes into an MGB and drove west through the Lincoln Tunnel to follow Interstate 80 toward a new life.

![]()